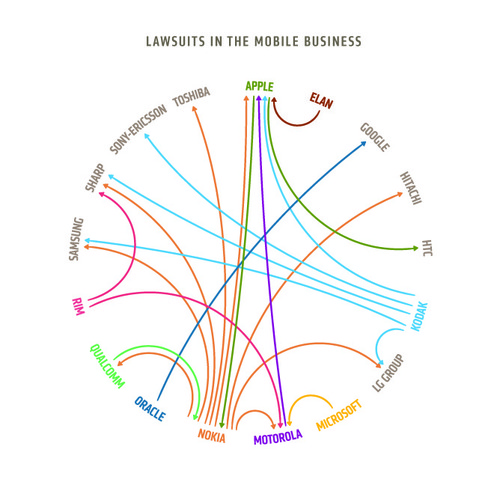

A lovely visualization by Design language that’s been making rounds connects a couple dots from recent posts on this blog. Somewhat randomly, I had been musing both about how Kodak had the foresight to invent a “consumer” digital camera 35 frickin’ years ago and yet how did the whole camera industry completely miss the boat (or iceberg as it were) on mobile technology?

I like this visualization because I’m not surprised to see the company with the least actual presence in mobile with some of the most outbound lawsuits*. It also shows that Kodak must have seen mobile coming, they’ve got the patents.

On my last post Scott Smith commented

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve met with a client who said, “well, we developed that back in 19xx, but we didn’t have the demand to do anything with it…”. Which means R&D ends up inventing random futures in various formulations at a 1000:1 ratio, then shelving them until an unknown window opens.

A lot of big innovation shifts don’t actually sneak up on us. My suggestion was that the necessary conditions and tipping points may be the only hard or even random part. It’s nearly as easy to be too early as it is to be too late with a new invention. Shifts (like the digital camera example) are often very well anticipated by any designer or engineer immersed in the field.

But what do you do as a firm if your best foresight poses fundamental existential business risk to your entire firm? Forget consumer demand, you’re also not going to see a lot of right-thinking managerial demand to productize those insights. What to do if you are Kodak in the sunset of the 20th century, when 90% of your business is making money from consumables that have no place in an inevitably digital future? Quite often, the very reason a disruption is so successful is because it democratizes a product or media by sucking a lot of money out of the system and/or transferring significant economic surpluses from producers to consumers. This kind of creative destruction is what drives growth and efficiency at the macro-economic level but it’s often catastrophic at the firm level for incumbents.

In the last decade Kodak’s stock price as methodically tumbled, the shares losing more than 95% of their value since their peak in the mid 90s. Kodak still comes out with new products and digital cameras. These business lines may well be fine and profitable, but they are also just a weak echo of the firms former dominance in photography.

So I guess my question for all the foresight gurus out there is this. What do you do when the best scenario you can see for your clients is a Kobayashi Maru?

We can see what Kodak did. A classic strategy, we’ve seen it all across the media industry as a great many incumbents try desperately to stuff the internet back in the tube(s): If you can’t turn the ship, sue the iceberg.

*Not to mention Nokia, another collapsing incumbent but that’s another story

Great post, and thanks for sharing that visualization. I recently had this happen where a client stated they were looking for “disruptive innovation”. Well, when it appeared, it was quietly ignored and shoved back in the bottle. At this point, I’m unsure how to confront the client with this fact and the subsequent behaviour it triggered internally. It’s an awkward position to be in, so I’m curious to find out how others have handled it.

This is exactly the same reason why Microsoft has so much trouble producing anything other than Windows and Office. The pressure to continue deriving profits from the existing profitable apps and existing customer base is intense, and doubly so because the corporation is public.

To deliver the new technology you must kill off the old, and when you do that you risk losing a large chunk of customers (they have to switch to something, either your new product or someone else’s, so why not shop around). You also risk losing disgruntled employees.

Every company I can think of in this situation has accepted the slow death that comes from continuing to milk the cash cow.

I think the only way out is to cleave off a new division within the corp, shield it from the old business, and give it the charter to innovate, even in ways that hurt the old business and existing customer base.